The earlier you find a cancerous mole, the easier the treatment and the better the outcomes. But it’s not easy distinguishing between harmless, benign moles and those that warrant further attention.

In recent decades, the incidence of skin cancer has increased in Australia. Two in three Australians will be diagnosed with skin cancer by the time they are 70 years old.

Non-melanoma skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, are the most common skin cancers but are less dangerous than melanoma.

In 2010, melanoma was the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia, with 11,405 new cases diagnosed. It is also the most common cancer diagnosed in Australians aged 15 to 39 years.

A number of characteristics are associated with an increased risk of melanoma, including:

- age

- number of moles

- skin type and colour (especially if you always burn and never tan in the sun)

- personal history of melanoma or other skin cancer

- freckles

- unusual-looking moles, larger than five millimetres

- red or light hair.

High levels of sun exposure and history of sunburn also increase the risk of melanoma.

Advances in treatment over the past three decades have improved the chances of survival. The five-year survival rate has increased from 85.8% to 90.7%. The prognosis is better the earlier melanoma is diagnosed.

Bad sunburn increases your risk of melanoma. Kevin O’Mara/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

By regularly checking your own skin, you may notice moles that are changing as well as identify new moles. A study of more than 3,500 Queenslanders with melanoma found that almost half of the melanomas were detected by patients themselves and a fifth were found by partners.

The features of melanoma to look out for are often referred to as the ABCD rule:

- Asymmetry

- Border irregularity

- Colour variation

- Diameter larger than five millimetres.

Doctors and the wider population have used this rule for more than 25 years to identify suspicious moles. But with the increasing diagnosis of smaller melanomas and border irregularity being a feature of many benign moles, these features are not always good predictors of whether a mole is cancerous or not.

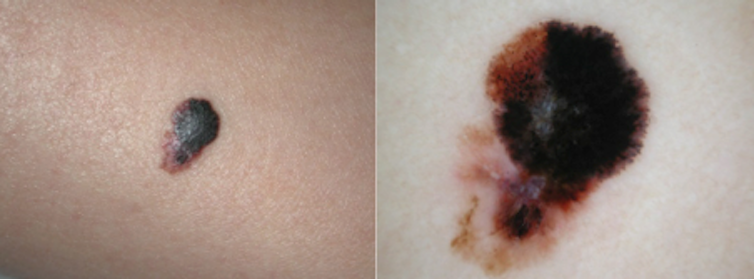

In 2011, a simpler AC (Asymmetry and Colour) rule was proposed for wider use by the community. While normal moles tend to be symmetrical and uniform in colour, melanomas tend to be asymmetrical and display multiple colours.

Asymmetry and colour variation typical of melanoma. Peter Soyer

Using this rule, people without any professional health care experience were able to correctly identify 93% of melanoma images.

Not all melanomas follow these rules and some are very difficult to identify. In particular, a type of melanoma called nodular melanoma is a fast-growing, aggressive form of melanoma, which has poorer treatment outcomes and survival.

Researchers in Melbourne proposed the addition of “EFG” (elevated, firm and growing for more than a month) to the widely known ABCD rule, to improve early detection of nodular melanoma. These melanomas often begin as a red nodule. While their appearance can be mistaken for a pimple, they are much firmer to touch. This should prompt further investigation.

Nodular melanomas are fast-growing and aggressive. Peter Soyer

If you’re concerned about moles with any of these features, consult your GP, who can refer you to a dermatologist if warranted.

If you’re at high risk, based on the risk factors listed above, check your skin regularly. Have another person (partner, family member or GP) check hard-to-see areas such as the back, neck and scalp.

Better melanoma detection

As awareness of melanoma has increased and consumers have taken a more active role in their own health care, the technological world has responded with new hardware to transform smartphones into diagnostic medical instruments and software designed to “autodiagnose” skin cancers.

Astute entrepreneurs have developed numerous mobile applications aimed not only at educating and calculating individual risk, but also enabling people to document, track and analyse their own moles.

But experts have raised questions about their accuracy. A recent study submitted images of 15 melanocytic lesions (five melanomas and ten benign moles) to five different mobile applications, to compare the risk grade allocated by each app (low, moderate or high risk for melanoma) with the clinical diagnosis.

Two of the five apps tested did not identify any of the melanomas. The other three apps detected 80% of the melanomas.

While the technology is exciting and it can be tempting to engage in this new mode of health care, be wary, particularly about applications costing money. The accuracy of many of these apps is questionable and could give false reassurance and lead to delayed diagnosis.

Research is continuing into combining the use of mobile dermatoscopes, a device using a light source and magnifying lens that can be attached to a smartphone to examine the skin, along with specialist advice.

Mobile teledermoscopes attach a light source and magnifying lens to a smartphone. Queensland University of Technology

Using such a device, people can take images of their own moles and store them to monitor changes in moles over time, as well as send them to a dermatologist for diagnosis. This process is called teledermoscopy.

So far, studies suggest consumers are able to identify suspicious moles and take high-quality images that are adequate for a specialist diagnosis. But specialists are concerned that consumers may overlook moles that would have been worthwhile photographing.

Researchers are now investigating the factors influencing wider application in the health-care setting. The benefits of consumer-led mobile teledermoscopy could include reduced waiting times, reduced costs, earlier diagnosis and improved treatment outcomes.

Mobile dermatoscopes are likely to become a popular smartphone accessory in the future. Until then, the best we can do is regularly check our skin using the ABCD/AC and EFG rules, and show any suspicious mole to a GP or dermatologist.

H. Peter Soyer and Anna Finnane are researchers at The University of Queensland. This article first appeared on The Conversation website and is reprinted under a Creative Commons licence.